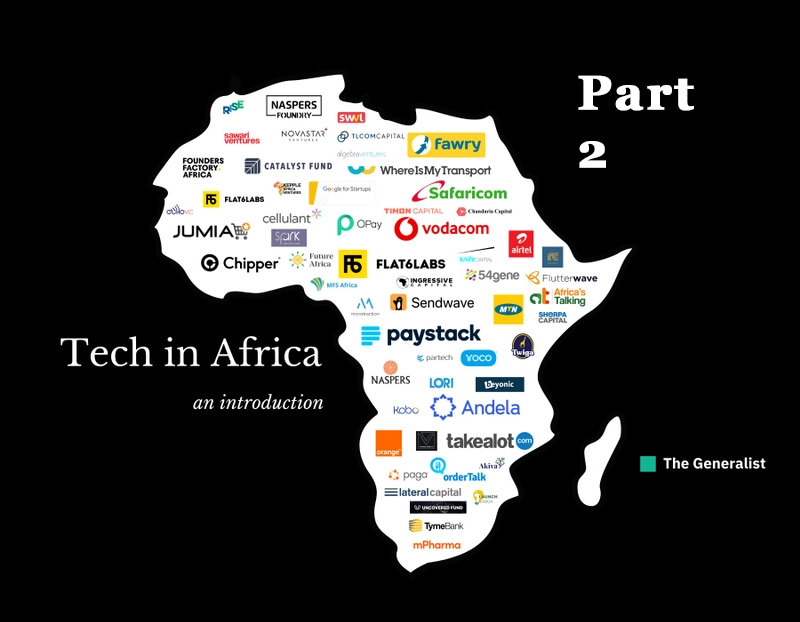

Analysis of the technology market in Africa: while China is investing billions in it, local authorities are slowing down growth. Part 2

Table of contents

Table of contents

How it works, who and why attracts multimillion-dollar investments from China and the United States, and why the authorities are hindering its development — in the retelling of The Generalist's analysis. Ending.

The end. Start here

African government policy

According to the publication, African authorities often adhere to the "outdated" views, and their decisions differ from region to region and often not only slow down the development of markets, they block new technologies, are in no hurry to issue licenses and are afraid of losing control.

First intercepts, then parses

In 2021, the Central Bank of Nigeria banned local financial institutions from carrying out any cryptocurrency transactions. Despite the fact that in 2020 the volume of crypto trading on regional exchanges like Yellow Card increased by 1840%, and half of the users were from Nigeria.

On the one hand, this is how the Central Bank retains control over the financial sector. On the other — hinders the development of the market in which Nigeria is the leader: it is its citizens who more often than others own digital assets.

In the US, only 6% hold cryptocurrency, and in Nigeria alone — 31%.

The authorities, however, are not limited to the digital space. In 2020, the Nigerian state of Lagos banned commercial motorcycle taxis from carrying passengers. The decision hit the operations of Okada, Pride, Keke and Gokada, but the latter adapted and switched from transportation to delivery.

In June 2021, the Nigerian government banned Twitter, but the authorities may change their minds, the publication believes. Before the pandemic, no bureaucrat would have held a virtual meeting, and now the government of Rwanda communicates with citizens through the public services website Reuters

Does not issue licenses

For example, in Nigeria, in order to open a business in the local savings market, companies must obtain permission from the authorities. However, this takes years, so they turn to the Central Bank: it issues a "super agent license" that allows them to temporarily provide their services.

Startups hope that during this time they will have time to prove themselves and thus get a license from the authorities faster. But the latter are in no hurry to issue it even to those projects that have been operating on the market for several years.

Wants to control everything

In East Africa, telecommunications firms are the most powerful. M-Pesa mobile banking alone accounts for more than half of Kenya's GDP. At the same time, 35% of its shares are owned by the government.

In West Africa, traditional banks dominate: they interact with governments, participate in export transactions and influence monetary policy. Thanks to their connections with the authorities, they can interfere with competitors and thereby maintain market leadership, The Generalist believes.

African startups entering new markets

Due to differences in language, culture and laws, managing a neobank in the two regions of Africa is not at all easy, the publication notes. Because of this, investors are more likely to choose startups with a single but large domestic market.

According to The Generalist, venture capitalists invest not so much in the development of the entire continent, but in the promotion of certain companies in certain markets.

Sherpa Ventures surveyed 30 African startups and found that South African and Nigerian companies with a single but large market (57 million and 210 million inhabitants, respectively) were almost twice as likely to raise capital as similar organizations in Ghana and Rwanda (29 million and 13 million).

True, even big players have to talk about expansion to convince investors. Egypt (100M) often positions its home market as a way to expand into North Africa and the Gulf region.

Small countries like Uganda (44 million) and Rwanda (13 million) have a harder time getting started, the newspaper notes. Attracting investments in the domestic market is not easy, and entering the big ones means competing with local leaders.

According to Sherpa Ventures, 79% of entrepreneurs seek to expand primarily to increase profits. To do this, they actively attract corporations as clients. Those, as a rule, already work in several markets, which startups may later enter.

One of the — Kenyan logistics project Lori. A key client in Kenya was the World Food Programme, with which Lori was able to establish itself in Uganda and South Sudan.

More than 50% of the surveyed companies decided to expand in the first two years of operation, often not having time to gain a foothold in the main market and not realizing that success in the new one depends on its laws, demand and competition.

That's why Sherpa Ventures found that 13% of startups left new markets: companies didn't meet the requirements of local authorities and didn't find experienced workers locally.

Foreign Capital

Despite the fact that investors began to actively invest in Africa in 2020, they showed interest back in 2015, and already in 2017, the volume of investments in the continent increased six times. Its markets seemed promising to local and foreign venture funds, although they could not fully argue the forecasts, the newspaper writes.

After the publication of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, Africa has also attracted socially transformative investment — in projects that, in addition to profit, create social benefits.

According to a survey by the Global Impact Investing Network, 59% of these investors own assets in emerging markets and invest most of their capital (21%) in Sub-African countries. Over the next five years, 52% of these investors plan to increase their investment.

China as the main investor

China invests the most in Africa — its largest trading partner: in 2019, the trade turnover between the states increased by 20% and amounted to 204.2 billion US dollars, and the total investment reached 46 billion US dollars.

Experts believe that with the help of large-scale injections, China wants to get local resources and dominate in various industries. So far, his involvement has benefited the African tech sector. However, the transfer of control into the hands of foreign organizations undermines the domestic ecosystem.

While fintech startups Paga and Crowdforce have grown their presence through their own work, OPay has been expanding thanks to multimillion-dollar investments from China. He eventually became the owner of the main share in African mobile banking.

Nigeria was in no hurry to protect domestic interests, notes The Generalist. Although the authorities limited the access of foreigners to licenses and forced them to cooperate with local entrepreneurs, otherwise they "sitting on their hands".

The Indian government, according to the publication, is acting more radically. Since 2016, the volume of Chinese investment there has been 12 times, and 18 out of 30 Indian billion dollar companies considered Chinese investors to be full market participants.

Despite the fact that investment helped development, India played it safe and banned 59 Chinese apps in 2020. The PRC, she believed, was using data from Indian companies to advance its agenda.

Government as an engine of investment

However, according to the publication, the authorities should not only protect the domestic market, but also attract capital — from both foreign and local investors. In this, according to The Generalist, Israel has succeeded: the state has about 205 venture capitalists, about 70 foreign companies and 60 corporate investors.

Africa has a lot of work to do, but the first steps have been taken, the publication believes. In 2018, to encourage entrepreneurship, Tunisia passed a "startup law" that set investment standards and promised to subsidize entrepreneurs' wages and provide tax breaks.

Misconceptions of investors

Although the volume of foreign investment is growing, investors often misunderstand how the ecosystem of the continent actually works. They forget that Africa — not a country with one market, but a whole continent with different regions.

Companies do not operate "all over Africa": they gain share in certain domestic markets.

Investors also doubt the identity of African projects and think that African markets can be valued using the same formulas that are used in the analysis of American companies.

Investors believe that Africa is copying others

In 2013, Sequoia stopped investing in Brazilian startups because it decided that most of them were copying existing companies. Many hold a similar opinion about African projects, but Africa, according to the publication, has gradually developed its own unique ecosystem.

In the first phase, startups emulated e-commerce giants like Amazon, Carvana, and Booking. However, there were no adequate payment instruments on the continent or access to them, Africans were not accustomed to paying upfront for shipping, and logistics were poorly developed.

In the second stage, entrepreneurs were inspired by Asian start-ups, which succeeded despite the lack of services and low income. Then Africans launched commonly used payment applications and messengers, and then added more expensive features to them: online shopping, lending and investing.

At the third stage, African startups no longer copy others, but strive to meet the realities of the local market. They improve financial and logistical infrastructures and change economic behavior.

An example of this — Sokowatch company. It allows small businesses in the shadow retail sector to buy goods on credit via SMS or app with same-day delivery.

Investors misjudge African markets

Despite the fact that the total population of Nigeria and Brazil is approximately the same — 206 and 209 million, respectively, in Brazil, more than 10 US dollars a day is spent by about 125 million people, and in Nigeria — only 3.7 million

Users of African neobanks keep less on deposit than residents of other countries of the world. According to the publication, the average African deposits about $200, while American Chime customers, according to 2019 data, deposit an average of $1,160 each.

In Africa, it is also difficult to determine the potential demand for a service. “We were able to raise $10 million because we thought our target market was 200 million people. Three years later, it became clear that in fact our product needed only 4 million, — says a Nigerian entrepreneur.

Socio-economic problems of Africa

Africa continues to lag behind in education, business, healthcare and government regulation, the newspaper notes. Therefore, to open up new markets and sources of income, it will need fundamentally new solutions.

Lack of schools and qualified teachers

Classes in schools in the region are overcrowded, and most institutions in Tropical Africa have closed due to the coronavirus. TV and radio lessons launched by the government cannot replace face-to-face classes, and alternatives like online courses are not available to everyone due to problems with the Internet, the newspaper writes.

By 2050, Africa will be the only region where the working-age population will continue to grow, the newspaper writes. However, most teachers are not qualified enough to train future specialists: in other states, 85% of primary school teachers received diplomas, in Tropical Africa — only 64%.

If the authorities want to capitalize on the upcoming demographic changes, they will have to create a more efficient education system, the publication believes.

Companies lack technological and financial support

Small and medium-sized businesses provide up to 65% of the continent's GDP and employ 85% of the entire workforce. However, the activity of many of them is still tied to cash: for example, in Nigeria they are used in 87% of transactions.

Entrepreneurs cannot yet increase the share of the digital economy: they do not have tools for reporting and increasing productivity, and there is also no access to loans. The latter, according to the publication, deprives companies of opportunities for growth.

It is difficult for Africans to buy medicines and get tested

If the population grows rapidly, the cases of diseases will increase, writes The Generalist. Today, however, half of Africans cannot afford even basic medicines. In middle- and low-income countries, generic drugs such as paracetamol cost 20 to 30 times the base price.

Despite the fact that the African pharmaceutical market is estimated at 40-60 billion US dollars, the continent accounts for only 0.7% of global spending.

It is difficult in Africa and with analyzes. Only 1% of primary health care facilities take them. At the same time, in 70% of cases it is impossible to make a diagnosis without at least one analysis. For 2021, eight out of ten countries with the worst healthcare — African. Without technology and investment, the situation will only worsen, the publication believes.

Africans do not have access to technology and forge documents

The launch of Safaricom's M-Pesa mobile bank in 2007 contributed to the development of African fintech, followed by Tala and Branch — services that provide loans to small and medium-sized businesses in Kenya and Nigeria.

However, they did not solve the problem with access to technology, the newspaper writes. According to the World Bank, about 66% of adults still do not have a bank account, and in sub-Saharan Africa, there are about four bank branches for every 100,000 adults.

The development of the financial sector is hindered by the falsification of identity cards. Because of this, the UK and New Zealand canceled the visa-free regime with South Africa for some time.

However, if Africa receives more investment and access to technology, it will be able to solve urgent problems and strengthen its position in the international market, the publication believes.

Other topics:

Other topics:

REAB Services

REAB Services

News

News

Useful tip

Useful tip